By J. Cody Nielsen and Jenny L. Small

Throughout its history, higher education has sought to introduce students to the perspectives of a global citizenship. The last few decades have seen students’ opportunities to experience these perspectives dramatically increase, as social media, technology, and world travel have all accelerated. To effectively educate students through a global lens requires institutions confront issues of inequity.

North American higher education has mainly considered inequities related to LGBTQIA, racial, and gender identities. Religious, secular, and spiritual identities have remained largely absent from conversations. This next decade of the 21st century offers a timely opportunity for higher education to reconsider its approach to this often-misunderstood area of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Making Practices Equitable

As readers, you might immediately notice the use of the nomenclature “religious, secular, and spiritual identities (RSSIs).” This terminology, broader than previously used terms such as “religious diversity,” “interfaith,” or “multifaith,” has slowly found its way into U.S. higher education after the Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (2017) advanced this language. We as authors encourage reconsideration of outdated terms and a movement toward the inclusive “RSSIs.” This language intentionally demonstrates the complexity of identities as well as the breadth of diversity in beliefs and practices which requires the provision of equitable and supportive systems.

Beyond language, of course, RSSI equity must be addressed through institutional policies and practices, as well as research and theory development. In the practice realm in the United States and Canada, the aforementioned “interfaith” has dominated the creation of dialogue and discussion programming to be engaged in by students, staff, and faculty, as well as civically minded activities such as building homes and cleaning up public areas.

Despite good intentions, without careful consideration, interfaith dialogue and discussion programming may unintentionally tokenize minoritized religious identities.

This is largely due to the Christian framework through which these activities may be created and implemented. The interfaith movement in the United States has too often failed to move the needle of RSSI equity. When considering this type of practice on campus, higher education professionals should examine if and how privileged religious traditions may dominate these activities. If the majority religion controls the form and features of these events, it is much more likely that missteps will occur, leading toward further distortion and “othering” of marginalized identities.

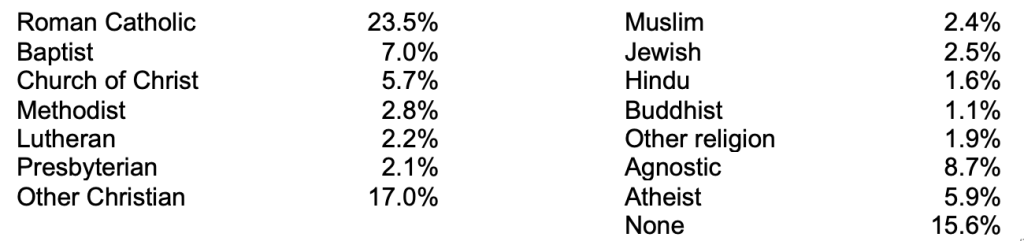

This othering effect can also occur through data collection. For example, surveys of student RSSIs may limit individuals from claiming the particularities of their identities. If we as higher education professionals create surveys that neglect religious minorities or cause them to feel misunderstood, we have created harm. In the chart below, we present data rom The Freshman Survey, a well-respected U.S. national survey which occurs each fall (A profile of freshmen at 4-year colleges, Fall 2017, 2019). In this sample from the 2017 survey, all categories on the left represent identities within the Christian religious community. On the right, non-Christian identities are broken down into general categories and broad religious identities. In an equitable setting, these latter identities would be particularized by denomination, in the same way Christianity is, so that respondents would be able to select their particular communities of practice. In addition, the categories of Agnostic, Atheist, and None fail to provide information about the religious cultures in which students were raised; likely, many if not most of them were raised as Christians or within a Christian culture. Categorizing them otherwise skews the survey results in ways many readers would not realize (Edwards, 2018).

Religious preference of first-year students at 4-year colleges, Fall 2017

A Critical Framework for RSSI Equity

The aforementioned items are but two of the many areas of RSSI equity that should be in consideration for the field of higher education. To provide a broader and more comprehensive perspective, critical theories must be developed to inform the policies, practices, and research within the field. The goal of critical theories is to be “concerned in particular with issues of power and justice and the ways that the economy; matters of race, class, and gender; ideologies; discourses; education; religion and other social institutions; and cultural dynamics interact to construct a social system” (Kincheloe & McLaren, 2002, p. 90). Understandings of other types of oppression led to the development of other critical theories, most famously critical race theory. These issues of power and justice also exist around RSSIs, but no critical theory had ever satisfactorily addressed this before.

Critical Religious Pluralism Theory

Newly developed by the second author of this column, Critical Religious Pluralism Theory (CRPT; Small, 2020) aims to address RSSIs utilizing this necessary critical lens. The goal of CRPT “is to acknowledge the central roles of religious privilege, oppression, hegemony, and marginalization in maintaining inequality between Christians and non-Christians in the United States (as analyzed through the medium of higher education)” (p. 11).

In short, CRPT aims for total social transformation to ensure a just and equitable society for all RSSIs.

In the interim, there are many steps that the field of higher education can take toward its own transformation.

CRPT offers a framework of seven tenets:

- CRPT declares that the subordination of non-Christian (including nonreligious) individuals to Christian individuals has been built into the society of the United States, as well as institutionalized on college campuses.

- CRPT critically examines the intertwined nature of religion and culture, and embraces an intersectional analysis of religious identity with race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, dis/ability, immigration status, socioeconomic class, and all other forms of social identity.

- CRPT exposes Christian privilege and Christian hegemony in society, as well as the related concept of the false neutral of secularism.

- At the individual level, CRPT advocates for a pluralistic inclusion of all religious, secular, and spiritual identities, recognizing the liberatory potential of these identities upon individuals’ lives.

- At the institutional level, CRPT advocates for the field of higher education to utilize a religiously pluralistic lens in all areas of research, policy, and practice, accounting for power, privilege, marginalization, and oppression.

- At the systemic level, CRPT advocates for religious pluralism as the means for resolving religious conflict in the United States.

- CRPT prioritizes the voices of individuals with minoritized religious identities and those with pluralistic commitments in the work toward social transformation. (Small, 2020, p. 62)

In order to make the seven tenets of CRPT usable by scholars and practitioners, each has been converted into a guideline. For example, guideline 5, which relates to institutional levels of change, asks:

Does the piece of research, policy, or professional practice in question advocate at the institutional level for the field of higher education to utilize a religiously pluralistic lens in all areas of research, policy, and practice, accounting for power, privilege, marginalization, and oppression? (Small, 2020, p. 68)

The following is an example of a policy that succeeds at putting this type of thinking into practice. At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, there is a specific committee dedicated to responding to and arranging religious accommodation requests. Called the Religious Accommodations Advisory Committee, it eliminates the need for students to directly request accommodation from their professors. It also places the effort required to organize the logistics of an accommodation on a separate group, rather than on the student or on the professor. This policy connects to Guideline 5 of CRPT, because it acknowledges that the existing systems on most college campuses place the needs of non-Christians underneath those of Christians. Christians automatically have their holidays off from school, but non-Christians do not. This policy works to rectify that. It is also proactive, not relying on minoritized individuals to ask for accommodation. Finally, the committee is made up of individuals from varied RSSIs, allowing for a greater understanding of different minoritized voices.

Making Your Own Work Equitable

Critical theories like CRPT, institutional practices like the Religious Accommodations Advisory Committee, and inclusive language like “RSSIs” are all elements of making higher education equitable for students of all religious, secular, and spiritual backgrounds. We encourage each reader to consider your own institutional or organizational policies, practices, and research studies to consider ways they could be made more equitable asking the question:

How can you reconsider your own institutional or organizational policies, practices, and research studies, in order to make them more equitable?

If you would like to engage in further discussion with one us, please contact us at j.cody.nielsen@convergenceoncampus.org or jenny.small@convergenceoncampus.org, or check out the Convergence website.

Dr. J. Cody Nielsen is Founder and Executive Director of Convergence on Campus and Director of the Center for Spirituality and Social Justice at Dickinson College.

Dr. Jenny L. Small is Associate Director for Education and Content of Convergence on Campus.

References

Allocco, A. L., Claussen, G. D., & Pennington, B. K. (2018). Constructing interreligious studies: Thinking critically about interfaith studies and the interfaith movement. In E. Patel, J. H. Peace, & N. J. Silverman (Eds.), Interreligious/interfaith studies: Defining a new field (pp. 36-48). Beacon Press.

Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education. (2017). Campus Religious, Secular, and Spiritual Programs. Author.

Edwards, S. (2018). Distinguishing between belief and culture: A critical perspective on religious identity. Journal of College and Character, 19(3), 201-214. https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2018.1481097

Kincheloe, J. L., & McLaren, P. (2002). Rethinking critical theory and qualitative research. In Y. Zou & E. T. Trueba (Eds.), Ethnography and schools: Qualitative approaches to the study of education (pp. 87-138). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

McCarthy, K. (2018). (Inter)religious studies: Making a home in the secular academy. In E. Patel, J. H. Peace, & N. J. Silverman (Eds.), Interreligious/interfaith studies: Defining a new field (pp. 2-15). Beacon Press.

A profile of freshmen at 4-year colleges, Fall 2017. (2019). https://www.chronicle.com/article/A-Profile-of-Freshmen-at/246690

Small, J. L. (2020). Critical religious pluralism in higher education: A social justice framework to support religious diversity. Routledge.